Findings

MRP’s IR1 is the improvement of the economic conditions of the IDPs and HCMs. The outcome indicators for this IR are: (1) number of displaced business owners with new or re-started business and (2) percentage of trained IDPs/HCMs gainfully employed. In the project’s TOC, this is one of the contributory factors to the self-reliance of the beneficiaries. To achieve this, MRP implemented business recovery grants, livelihood microgrants and training workshops.

Document review data regarding MRP’s performance on IR1 indicators suggest that the project has helped 1,963 business owners to start a new business or re-start their previous business. There are 3,117 individuals who benefited from business recovery grants. MRP has provided livelihood opportunities to 8,350 IDPs and HCMs through its livelihood micro-grants. Moreover, there are 1,336 business owners who benefitted from enterprise management-related training and workshops. Refer to Annex 12 for the performance of MRP in relation to the project indicators.

The team examined income and employment-related variables in the endline survey to gain understanding on how MRPs outcomes and outputs indicators performance translate to the improvement of the economic conditions of the beneficiaries.

INCOME-RELATED VARIABLES

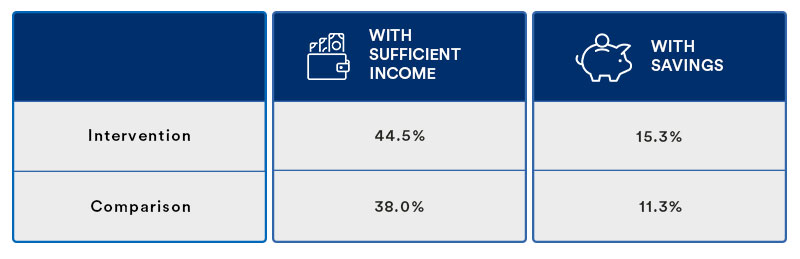

The team finds that the proportion of endline survey participants who reported that their income is sufficient to meet the basic needs of their families (e.g. food, medicine, children’s education) is higher among the participants who received MRP interventions (44.5%) than among the participants from the comparison group (38.0%) as shown in Figure 2. In the same manner, those who reported that they have savings is higher among survey participants who received MRP interventions (15.3%) than among the comparison group (11.3%).

The team further finds that the proportion of MRP beneficiaries who indicated they have sufficient income to meet the needs of the basic needs of their family (44.5%) is higher compared to the finding that involved the general population in BARMM (19.0%). Moreover, MRP beneficiaries’ economic conditions as discussed above provide a positive picture compared to the general economic landscape in the region during the pandemic. For instance, government report suggests that the number of households receiving salaries has declined and the incomes from farms and business in the region have generally plummeted during the time of the pandemic.

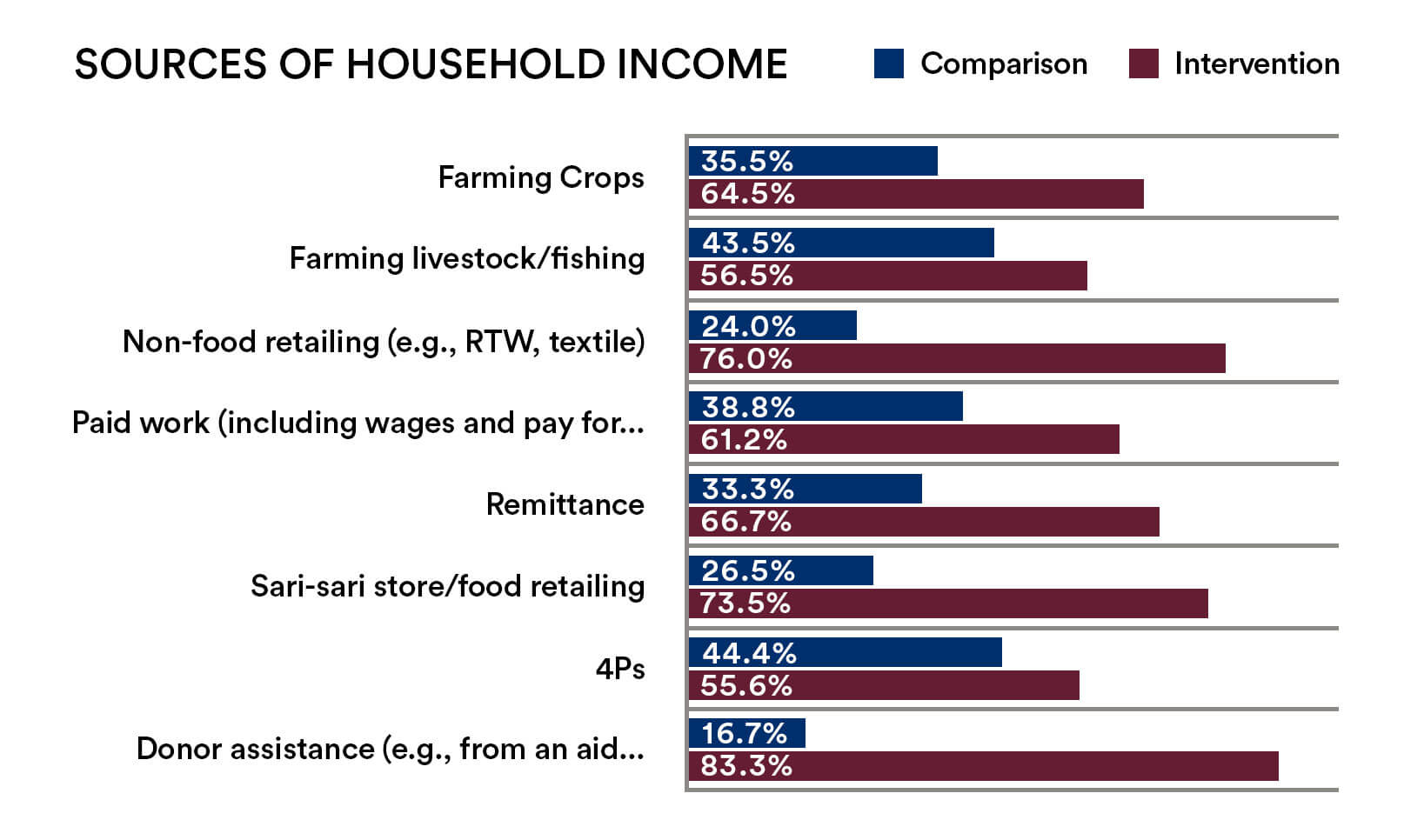

The evaluation team looked at the sources of household income of both the MRP beneficiaries and comparison group. Figure 3 shows that there are more MRP beneficiaries who are engaged with income generating activities such as crop and livestock farming (56.5%), non-food retailing such RTW and textile (76.0%), food retailing or sari-sari store (73.5%), and paid work (61.2%).

Box 3 contains the story a couple whose dressmaking business was devasted by the Marawi siege. Their story shows how MRP’s grant that provided them with sewing machines helped their family surmount the challenges brought about by the pandemic.

Box 3. Surviving the aftermath of Marawi siege punctuated by the Covid 19 pandemic

(During the Marawi siege, the Christian wife and husband IDPs from Marawi City evacuated to Iligan City. As entrepreneurs, master cutters and makers/tailors of wedding gown and suit, they had a space near Padian Market in Marawi City and have Meranaos customers. Now, in Iligan City they continue their trade in a much smaller space and continue to have Meranao customers from Marawi City.)

We grew up in Marawi. Before the siege, we had 12 dressmakers and tailors and we were renting a two-storey building and installed 12 heavy-duty sewing machines and two zig zaggers. In Marawi, we both were just cutting the patterns and our hired dressmakers and tailors were the ones doing the sewing. Business was very good with our Meranao customers who preferred our services as they kept having repeat orders. We prefer to live in Marawi since we have adjusted well there.

It took a year when we were allowed to go back to Marawi. All our machines were destroyed, clothing materials scattered and the P300,000 cash we kept at our shop was gone. Everything was wasted by the siege. That was not easy for us to accept.

The government gave us cash assistance of P73,000 for the industrial sewing machine that we bought and used now along with the zig zagger and clothing materials. Meanwhile, as members of CSG, MRP gave me and my daughter sewing machines, clothing materials and other sewing paraphernalia. These are now part of our present business. MRP’s assistance was good timing: at one point during the pandemic, the sales from the face masks we were sewing was our main income. Our income kept our lives going during that very challenging time. In addition, many of our long-time customers, our contemporaries when we were children also assisted us with cash to help us go on with our sewing business, something we never expected they would do.

The building owner in Marawi City where we had our sewing business asked we are intending to go back, and we said yes. Thus, we are waiting for the time and the opportunity so we can continue our sewing business in the same location in Marawi, where we grew up. We hope the time is soon.

Employment-related variables

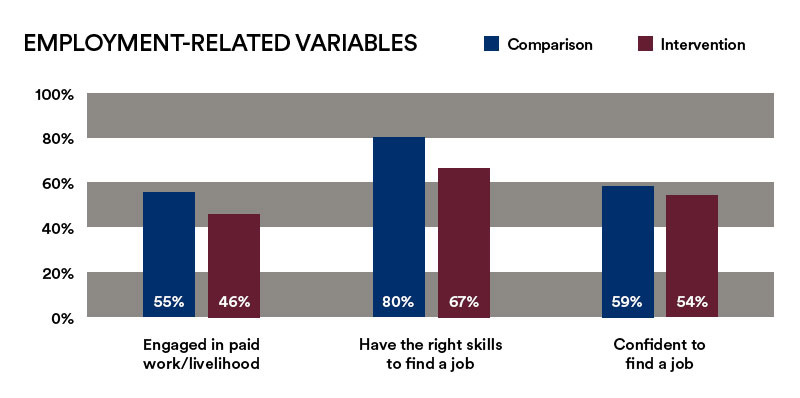

The endline survey data shown in Figure 4 suggest that there are more MRP beneficiaries than members of the comparison group who indicated that: (1) They are engaged in work/livelihood that pays them money (55%), (2) They have the right skills to find a job (83%), and (3) They are confident in finding a job in case they would lose their present (59%). An inferential analysis suggests that the proportion of MRP beneficiaries is significantly higher in terms of engagement in paid work/livelihood (p=0.024) and having the right skills to find a job (p=0.000). These imply that MRP’s interventions in the form of business/livelihood grants and training workshops have expanded employment opportunities of the IDPs and HCMs.

MINDA’s assessment of the impact of COVID-19 particularly the findings on BARMM indicated that: “BARMM has geographically dispersed provinces that makes the movement of people and goods time-consuming, difficult, and costly. The limited movements of people and goods that ensued have ultimately prevented the growth of the regional economies in Mindanao.” In view of these realities, the following narratives from MRP beneficiaries highlight the economic relief that the project has afforded:

-

“The hijab we made from the fabric earned us Php19,950.00. So far, our profit has reached Php40,000.00. All members received their share. We are now on our fifth cycle.”

(KII, IDP Leader, Ditsaan Ramain)

-

“I have seen during beneficial monitoring that beneficiaries have improved their houses. Those who engaged in selling groceries have available inventory in their sari-sari stores.”

(KII, MERL, Plan International)

The economic outcomes of MRP are important considering that the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted not only in a health and life crisis, but also a deep economic recession. In fact, the Philippines experienced a -8.3% gross domestic product growth rate in the fourth quarter of 2020 and -9.5% for the entire year. The employment-related outcomes discussed above indicate that MRP addressed to some extent the socio-economic needs of the beneficiaries brought about not only by the Marawi crisis but by COVID-19 as well. This is relevant to the findings of JICA (2020) suggesting that jobs and resumption of agricultural activities are among the potential COVID-19 recovery measures that the constituents of BARMM indicated.

The discussions above imply that MRP’s business and livelihood interventions have stimulated economic activity among the beneficiaries amidst the economic impact of the pandemic. In particular, the in-kind grants and the trainings that MRP provided its beneficiaries have contributed to the improvement of their economic conditions. Considering that Covid-19 generally resulted to widespread loss of livelihood and increase in poverty among displaced population, these present results show that MRP provided economic relief to the beneficiaries. This is succinctly corroborated by the following KII excerpts indicating how the trainings and in-kind grant helped beneficiaries:

-

“The members of our CSG have a chance to benefit from the projects we received from MRP. And they received training that helped them earn a living.”

(KII, HCM leader, Women CSG, Buadiposo Buntong)

-

“MRP has helped us through the provisions of sewing machines and trainings. The income we derived from our products augmented our families’ daily needs, especially for the school expenses of our children.”

(FGD, Women CSG Members, Marantao)

Box 4 shows the experience of a family who became IDPs due to the siege. They travelled as far as Cebu to seek recovery. Their sojourn back to Iligan proved to be beneficial as they received assistance from the government and from MRP. It helped them to eventually commence their journey towards recovery.

Box 4. Confronting Business Recovery as IDP

(The Marawi siege took place three days before the start of Ramadan. As a practice, a 30-day food provisions were stock at every Muslim household since unnecessary travels are discouraged. On the business side, Meranao entrepreneurs stock their merchandise and material inventories in preparation for Eid al-Fit’r feast that also takes days of ‘buying spree’ among customers.)

We are a wholesaler, so we usually keep our inventory level every three days. Our wholesale mobile phone business was doing very good. At the time of the siege, our family’s business inventory in Marawi was about PHP4 million.

We evacuated to our hometown in Mulondo, to spend the Ramadan. We tried our luck in Cebu City. We engaged in the night market selling mobile phones and gadgets. We gave it up after three months as the income was not enough for our daily provisions and to pay the rentals. We also had a problem with the landlord who not accept IDPs as apartment renters. We left Cebu and settled in Iligan City, where we received cash assistance of P73,000 from the government.

Later, my textile businessman uncle and I jointly received P200,000 worth of textile from the MRP. We chose textile because the release was faster. MRP found difficulties in procuring mobile phones and gadgets for my business. I eventually sold my textile share of inventory to my uncle and continued with my mobile phone business.

Despite the general dislike of the Iligan residents to the Marawi IDPs, my business continues to expand: from one stall (2mx3m), I now have the adjacent three stalls. Our income is now covering our family’s needs. We have five children. I got married at 13 and I now have a college graduating daughter.

MRP’s IR2 focuses on the strengthening of the social cohesion of IDPs and HCMs. MRP’s AMELP indicates that social cohesion refers to two intertwined features of the society which may be described as the absence of latent social conflict and presence of strong social bonds. MRP focuses on areas where there is a significant concentration of IDPs as a result of Marawi siege and intends to provide venues to decrease if not eliminate polarization between the displaced and the host communities.

CONTRIBUTION TO PERCEPTIONS ABOUT POLARIZATION

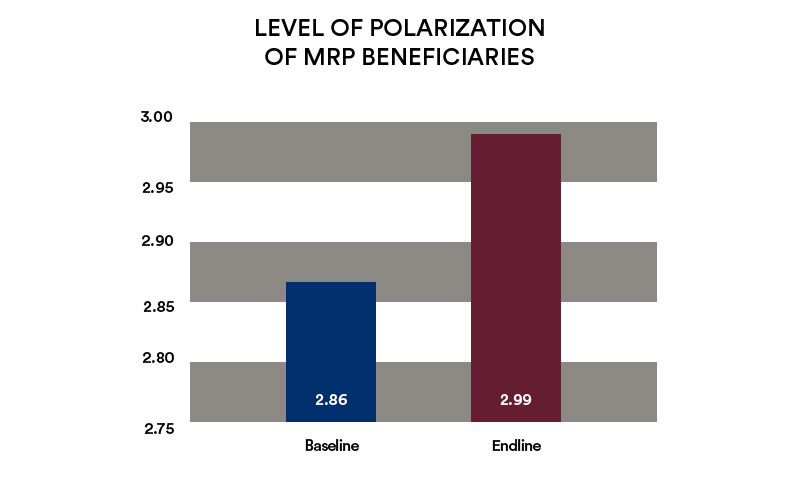

Polarization is conceived as a dimension of social cohesion. In the context of MRP it is defined as the fragmentation of a community depicted by trust (or lack thereof), and attitude in working together. This is specific between the IDPs and HCMs. Level of polarization in MRP is measured using a 4-point Likert-type scale consisting of 15 items. Overall, high scores in the polarization scale suggest positive views that the community is not polarized or is not fragmented.

The team finds that MRP beneficiaries’ overall perception of polarization has significantly improved at the endline (p=0.020). The significant increase in the scores of the beneficiaries from the baseline (Mean=2.86) to the endline (Mean=2.99) suggests that the beneficiaries are perceiving significantly lesser polarization or fragmentation in the communities they are living in at present.

The positive outcome on beneficiaries’ polarization perceptions indicated above contributes to the formation of social cohesion. Moreover, it is worth noting that a number of polarization indicators (e.g. differences in tribes, differences in religion) in this evaluation are associated with the notion of socially divisive influences outlined in the social cohesion discussion of OECD. This aspect is essential since social cohesion and the absence of socially divisive influences are viewed to be contributory to desirable development outcomes such growth, poverty reduction, stability, peace and conflict resolution (OECD, 2011).

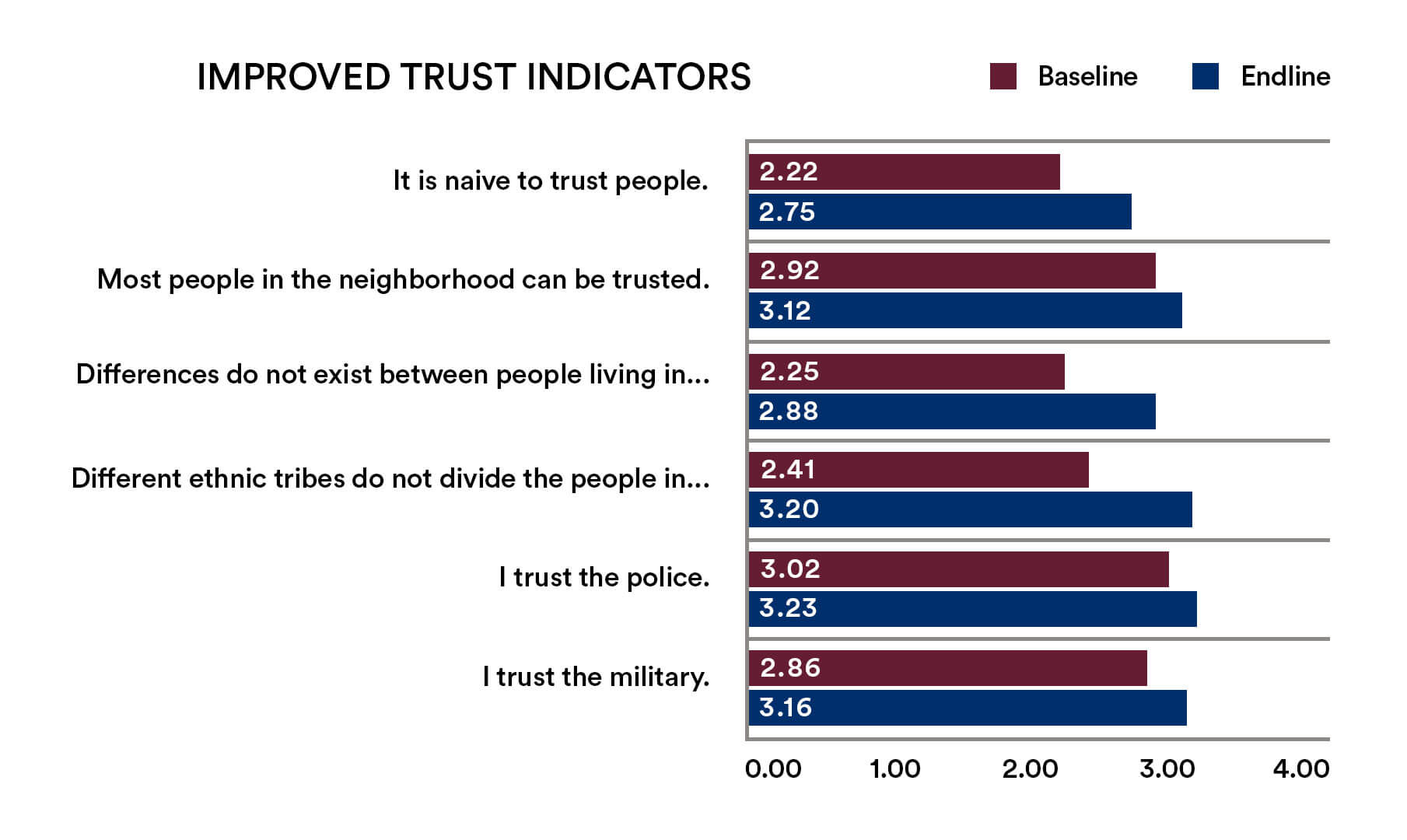

CONTRIBUTION TO PERCEPTIONS ON TRUST

The evaluation team further examined specific trust-related indicators in the polarization tool. This allowed the team to gain more understanding on the trust dynamics among the beneficiaries. The result of our analysis revealed that MRP beneficiaries’ level of trust has significantly increased in the endline (p=0.046). Moreover, the figure shows that MRP beneficiaries’ level of trust is significantly higher than the comparison group (p<0.001). The effect size generated in the analysis (d=0.481) suggests that MRP interventions have a medium or average effect contribution to the improvement in the trust level of the beneficiaries.

Figure 7 shows that there are improvements in the following indicators of trust at the endline: (1) Trust in people and neighbors; (2) Perception of existence of differences in the community between people and tribes; and (3) Trust in police and military.

The trust indicators above can be associated with the notion of horizontal trust between citizens. The observed improvement in these indicators is essential since the notion of horizontal trust between citizens is perceived to be a resource that enables societies to overcome the basic problems of collective action. Moreover, collective action is needed for the CSGs to continue to advocate and pursue their vision and aspirations even after the end of MRP. It is interesting to note that MRP beneficiaries rated the indicator suggesting willingness to work with IDPs/HCMs in implementing projects (Item 16) relatively higher. This may be viewed as a seed to the collective action that the beneficiaries need to manifest, particularly in sustaining the gains of MRP interventions after project ends.

Trust also has a prominent place in economics literature with the basic idea that it is a way to reduce transaction costs. Moreover, trust between citizens has also been empirically shown to be strongly correlated with economic growth.

The aforementioned findings suggesting improved trust levels particularly in police and military by MRP beneficiaries can be viewed vis-à-vis the argument suggesting that “in a risky society”, risks can only be overcome by placing trust in fellow citizens and the roles they fulfill in the social system such being a police personnel, social workers or bank advisor (Beck, 1992; as cited in Larsen, 2014).” This is important since trust in this point of view is conceived to be critical for institutions such as the market, democracy and even the state to function accordingly (Larsen, 2014). Improved trust levels particularly in police and military are all the more important considering the complex nature of the environment (e.g., political, economic) where MRP is situated.

MRP’s interventions served as opportunities to bring together IDPs and HCMs and helped re-establish existing social relationships and networks. The following excerpts from the KIIs with project beneficiaries and stakeholders show key factors that contribute to harnessing further the trust between and among IDPs and HCMs in MRP areas:

-

“We accept IDPs because they are Muslims, and Maranaos. They are IDPs now but we experienced their situation in the past.”

(KII, Barangay Captain, Ditsaan Ramain)

-

“We have no issues with the IDPs here because they are our relatives. Some of them have old houses here.”

(FGD, Women CSG Member, Buadiposo Buntong)

-

“Based on our experience, we don’t have conflicts between HCMs and IDPs. They work together in our community.”

(KII, LGU MPDC, Buadiposo Buntong)

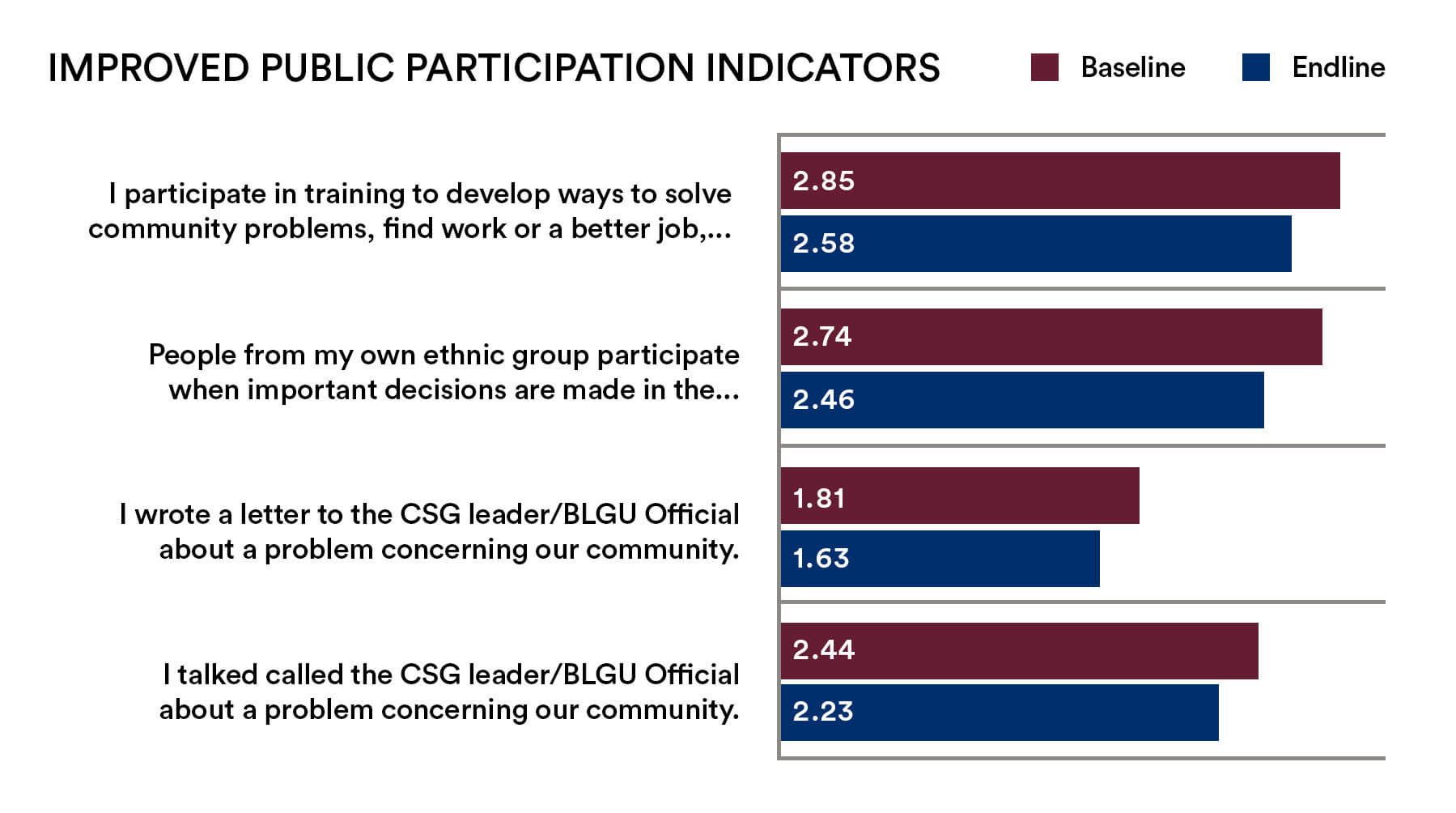

CONTRIBUTION TO PUBLIC PARTICIPATION

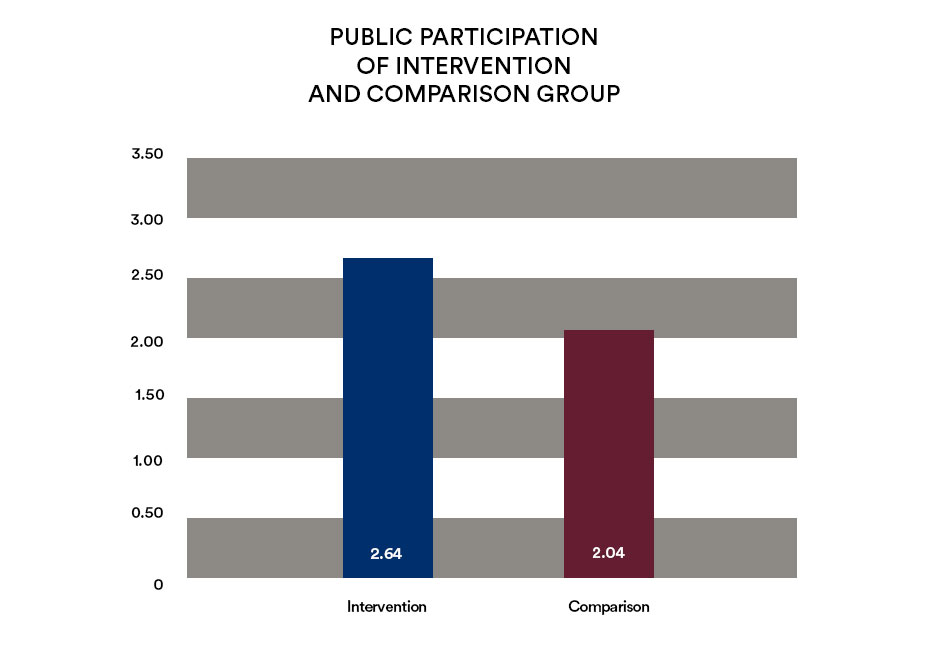

Another component of social cohesion refers to IDPs and HCMs civic engagement. To assess result towards this end, MRP looks at IDPs and HCMs’ perceptions of public participation. The inclusion of this component is based on the argument that regardless of the kind of political system in place, the harnessing of civic participation and feedback are essential if growth processes are not to be derailed. Accordingly, giving space for dissenting voices is fundamental to the creation of a sustainable, socially cohesive society. In the context of MRP, public representation includes participation and involvement (i.e., as member or officer) of displaced/host community members in CSGs, local special bodies (i.e. health boards, school board, environment boards, etc.), and local government. This is measured using a 4-point Likert-type scale that gathers data on their participation and involvement in community affairs such as CSG meetings and barangay activities.

Based on the endline survey, the team finds that the MRP beneficiaries have a high level of participation (Mean=2.64) while the non-MRP respondents have low (Mean=2.04). Further analysis revealed that the level of participation of MRP beneficiaries is significantly higher than the comparison group (p=0.000). The effect size from the analysis suggests that MRP interventions have a large effect (d=1.113) on the level of participation of the beneficiaries.

The item-level analysis shown in Figure 9 reveals that there is improvement on indicators related to communication with CSG and barangay leaders about community problems. This involves writing (Mean=1.81) or personally talking (Mean=2.44) to their community leaders about problems they have observed in the community. There is also improvement on indicators related to their participation in community decisions and training. This involves attending trainings for employment and meetings to address problems in the community (Mean=2.85) and community decision making (Mean=2.74).

These results suggest that MRP beneficiaries have improved their level of participation in community affairs including CSG-related activities. They have also improved the extent that they communicate with authorities and community leaders including their CSG leaders and BLGU officers. It is likely that these improvements are attributable to the social cohesion interventions provided by MRP to the CSGs such as the community improvement and civic engagement grants. Through these grants CSGs are trained how to develop their advocacy agenda and how to communicate them to pertinent local bodies.

The following narratives corroborate the survey results above. The excerpts show that the CSGs and their members are now able to represent themselves in local bodies and are now able to engage government officials in their projects:

-

“The CSGs have made requests from the municipal LGUs. They start to coordinate directly with them. Compared to before, they handle this now on their own. The relationship between LGUs and CSGs is open. This paves the way for greater LGU support.”

(FGD, Maradeca)

-

“When there are activities, for example when the projects are received, the chairwoman and the barangay councilors are there as witnesses. The relationship is close because the whole barangay is planning, talking as a group.”

(KII Buadiposo Buntong, HCM leader, CSG women)

Moreover, the narrative below shows an observation of a beneficiary depicting MRP’s role in promoting social cohesion among the beneficiaries through participation in project implementation:

-

“I have observed that apart from the economic and financial benefit, the social interaction among ourselves has also improved. Because without the MRP, the people here would not meet since there’s no reason for them to do so. The interaction with other people has been intensified because of the project activities.”

(KII, HCM leader/Women CSG, Buadiposo Buntong)

The findings above could serve as impetus for the formulation of effective public policies intended to address the needs and aspirations of the beneficiaries particularly the IDPs. On one hand, the IDPs and HCMs need to up the ante in lobbying their needs and aspirations which would require them to effectively communicate and actively participate in local bodies.

On the other hand, the LGUs also need to provide the space to hear their voices. This is consistent with the development perspective espoused by OECD (2011), which suggests that: “If the society integrates minorities, has a relatively strong sense of belonging, and provides opportunities for upward mobility, the effectiveness of its public policies will obviously be greater than in socially fragmented societies”.

Box 5 contains a story of a youth CSG that showed enhanced public participation by becoming part of the municipal and provincial youth federations. In effect, they made meaningful contribution to the development of their community.

BOX 5. COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENTS TOWARD BUILDING YOUTH FORMATION AND INCREASING PUBLIC PARTICIPATION

“Our meetings served as opportunities to establish relationships between and among youth IDPs and host communities,” says Asniah Sarip, the Chairperson of Masakaw Youth, composed of IDPs and HCMs with Sangguniang Kabataan (SK) members, one of the community solidarity groups in Barangay Basingan, Bubong, Lanao del Sur.

Formed in January 2020, the all-youth group CSG ventured into chicken and duck production as its livelihood project. Asniah and the members expressed gratitude for the community grant and the other interventions they received from MRP. The various CSG processes allowed them to work together to address issues affecting them and provided them with additional skills, especially in livestock and organizational management. They viewed the assistance and support of MRP as the main catalyst for their formation. Ashniah maintains that “MRP has redirected them to acquire new sense of purpose as young people for their own welfare and towards contributing positively to their community.”

The Masakaw Youth is now a member of the municipal and provincial youth federations. Asniah looks forward to more meaningful public participation of the youth where they can be formally represented and their issues are heard and addressed.

As part of evaluating the effectiveness of the project, the team examined how MRP’s development interventions have contributed to the reduction of social gaps.

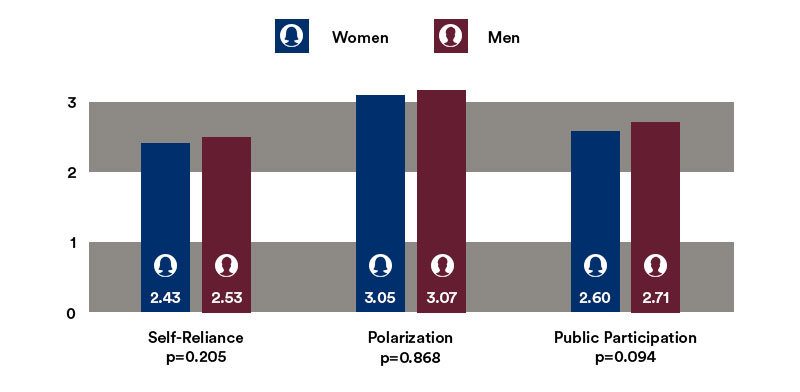

GENDER ANALYSIS

Firstly, we examined the impact of the interventions on women, particularly in their level of self-reliance, polarization, and public participation. Comparative analysis of survey data shown in Figure 10 suggest that the women beneficiaries have statistically comparable level of self-reliance (p=0.205), polarization (p=0.868) public representation (p=0.094) with men. This means, for example, that the women are as self-reliant as the men during the endline. This is an improvement from the baseline where women have significantly lower self-reliance than men.

The KII narrative below further illustrates how the livelihood grant that an all-women CSG received from MRP has allowed a mother to augment the income of their family:

-

“Before MRP, only my husband had a source of income. It was hard. With the livelihood support I got from MRP, I am earning Php 300.00-500.00. I used it for medicine and food. This seems not that much, but it has helped a lot.”

(FGD, Women CSG Member, Buadiposo Buntong)

The reduction in the gap between women and men in MRP outcome measures discussed above can be viewed as a positive development considering empirical data suggesting that women tended to absorb the shocks brought about by the pandemic. This is pointed out by the UN Women organization saying:

-

“Women are being hit hard by the fallout of the pandemic. Because they typically earn less, have fewer savings and hold less secure jobs to begin with, women are particularly susceptible to economic shocks in general. The pandemic has devastated feminized sectors like hospitality, tourism and retail, depriving many women of their livelihoods. Across all regions, women have been more likely to drop out of the labor force during the pandemic.”

IDP-HCM ANALYSIS

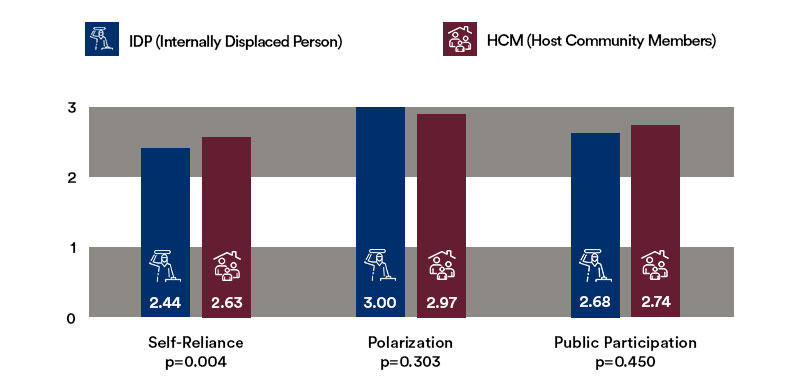

Secondly, the team examined the endline survey data between the IDPs and HCMs. The team finds that the IDP and HCM project beneficiaries have statistically comparable self-perceptions in terms of their level of polarization (p=0.303) and level public representation (p=0.450) at the endline as shown in Figure 11. The reduction in the gap is influenced by the improvement in the perceptions of the IDPs in these social cohesion-related outcomes. For example, the results reveal an increase in the IDPs public participation. This finding suggests that MRP has addressed the public participation disparity between the IDPs and HCMs that was found out during the baseline assessment.

This finding implies that MRP has addressed essential needs of both the IDPs and HCMs. This provides support to USAID’s do-no-harm approach wherein it recognizes that “while the activity is focused on providing durable solutions for IDPs, as part of a DNH approach, the implementer must ensure that this is not achieved at the expense or exclusion of other, non-IDP members of the community.” Moreover, this is parallel to USAID’s recognition about the sensitivities surrounding the project implementation and therefore interventions that may be deemed culturally inappropriate or counter-productive should be avoided.

Project stakeholders have also noted the essentiality of the beneficiary targeting that MRP implemented. A number of stakeholders have expressed their appreciation regarding the inclusion of both IDPs and HCMs in the project. The narratives below show the value of including the IDPs and HCMs as project beneficiaries:

-

“The beauty of MRP is that not only the IDPs from Marawi were targeted, but also the host communities. They made sure that the host community and IDPs can work together. I think this approach is important – that they both benefit from the projects.”

(KII, Municipal Administrator, Bubong)

-

“After being displaced, we never thought we would have the opportunity to be part of a community again, let alone vote for our chosen candidates in any election,”

(Youth leader, Lumbatan, MRP Success Story, AR 2021, p70)

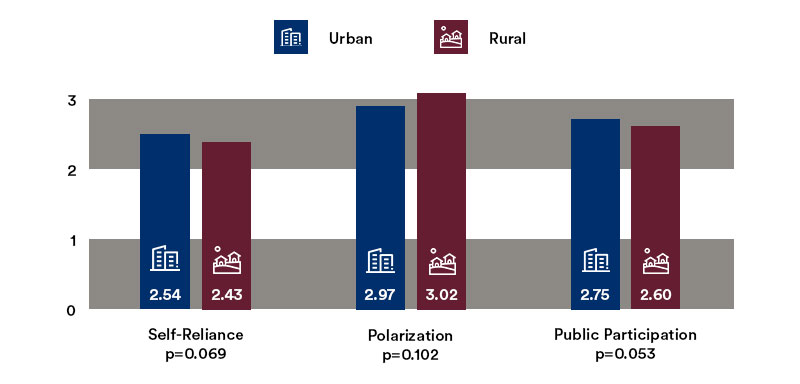

RURAL-URBAN ANALYSIS

Thirdly, we examined if the benefits of the project have been felt among beneficiaries from the rural and urban areas. We found out that the beneficiaries from the urban and rural locations have comparable self-perceptions about the level of polarization (p=0.102) in their present communities at the endline as shown in Figure 12. In particular, beneficiaries from the urban and rural areas both agree/strongly agree that polarization does not exist in the community where they are residing. This finding addresses the baseline result where beneficiaries from urban locations had been found to more likely indicate that polarization and fragmentation exist in their communities.

Moreover, analysis of the survey data reveal that the gap in public representation between beneficiaries from the urban and rural locations has been reduced (p=0.053) at the endline. During the baseline assessment, participants from the rural areas were noted to have significantly better public participation self-perceptions. Hence, it can be deduced that the social cohesion interventions that MRP implemented fostered improvement in public participation especially among the IDPs. Annex 14 contains the actual quantitative analyses results.

MRP’s results framework in Figure 1 indicates improvement in the self-reliance of the IDPs and HCMs as the project’s manageable impact. Self-reliance is defined as the social and economic ability of an individual or community to meet its essential needs in a sustainable manner. This is based on the two IRs of the project, namely: (1) improved economic conditions and (2) strengthened social cohesion of IDPs and host community members. The evaluation team utilized the same tool utilized during the baseline assessment to measure self-reliance IDPs and HCMs. To examine the project’s contribution to the self-reliance of the beneficiaries, the team performed baseline -endline analysis and intervention-comparison analysis of self-reliance survey data.

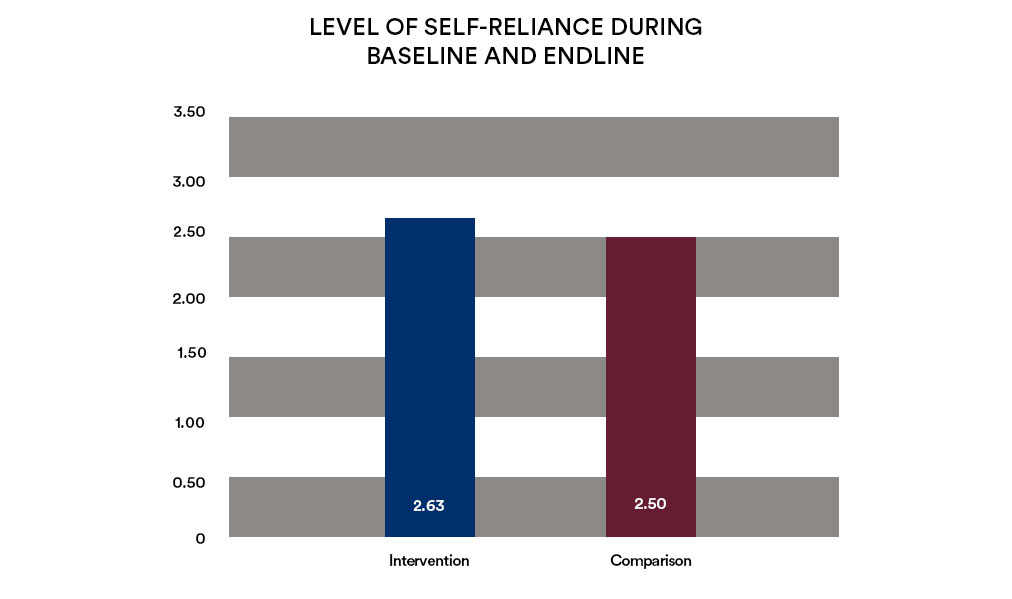

BASELINE-ENDLINE ANALYSIS

A descriptive analysis of the endline survey shows that the self-reliance of MRP beneficiaries remained high (Mean=2.50) as shown Figure 13. This is despite the adverse effects of the COVID-19 on the economic conditions of Mindanao households and their livelihoods due to restrictions in mobility and decline in financial security based on 2021 data (n=1,805).

Considering that most of the indicators of self-reliance in the survey are expressed in economic terms (e.g. The income I earn from my job/livelihood is sufficient to cover the basic needs of my family), the impact of the pandemic would have decreased beneficiaries’ self-reliance. However, the team finds that this is not the case. While there is an observed decrease in the beneficiaries’ level of self-reliance in the endline as shown in the figure, the magnitude is negligible or is not statistically significant (p=0.231). The non-significance of the decrease implies that the development interventions of MRP (e.g. livelihood grants) may have “cushioned” the beneficiaries from the economic shocks brought about by COVID-19.

The qualitative data from KIIs with MRP beneficiaries corroborate these findings. One beneficiary attributed the improvement in her family’s economic condition to her gains from the handicrafts business she is operating out of MRP’s business recovery grant. Prior to the grant, she did not have the means to send her sons to school. The following is the excerpt from the interview:

-

“If we compare our situation before and now, now is better. For example, my two sons who stopped schooling for two years are now enrolled. The income we have from the handicrafts that we make helped in buying the needs for their studies.”

(KII, Business Recovery Grant Recipient, Marawi City)

Another beneficiary expressed how the livelihood grant that their CSG received sustained them during the pandemic. The beneficiary even mused that their income from the livelihood grant was their means of meeting the needs of their family during the height of the pandemic.

-

“At one point during the pandemic, the sales from the face masks that we made using the sewing machines granted to us was our main income. Our income kept our lives going during that very challenging time.”

(KII, CSG Member, Brgy. Cabili, Iligan City)

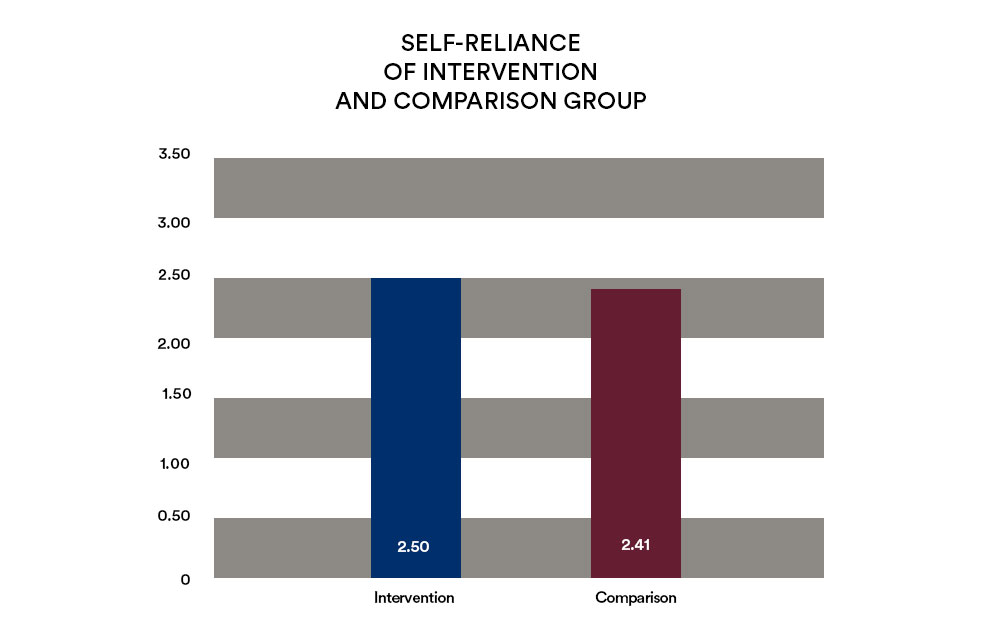

INTERVENTION-COMPARISON GROUP ANALYSIS

The team performed a comparative analysis of MRP beneficiaries perceived self-reliance and that of the comparison group. This was done to examine beneficiaries’ self-reliance appraisals in relation to other individuals who also experienced the same external factors. The result of the analysis indicates that MRP beneficiaries have slightly higher self-reliance at the endline as shown in Figure 14. While the difference in the self-reliance levels of the groups do not significantly differ (p=0.102), the result suggests that the MRP’s interventions contributed to the higher appraisals of the project beneficiaries.

MRP’s contribution to the self-reliance of the beneficiaries is further illustrated by the KII excerpt below which shows how the income from a business recovery grant helped a father meet the needs of his family:

-

“MRP’s assistance really helped my business. I was able to buy a “bongo” (delivery truck) and a mini-truck. As a result, I was able to send my children to school and meet my family needs.”

(KII, BRG Recipient, Lumba Bayabao)

MRP’s AMELP indicates that IDP’s durable solution is the “high-level” of the project. Moreover, the project conceives local integration of IDPs as the durable solution. While this present evaluation does not delve into the impact of the project in technical sense, the team explored how the project’s interventions have facilitated IDP’s durable solution.

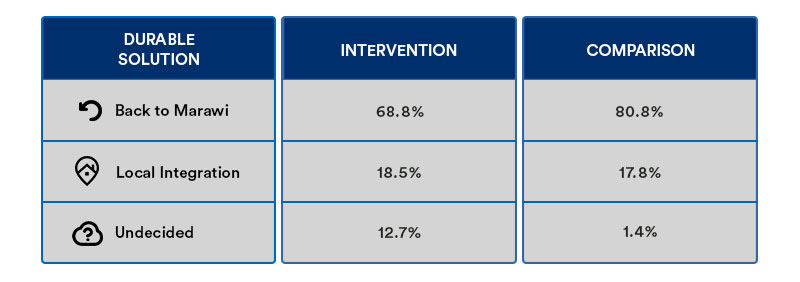

Figure 15 shows that the majority of the IDP beneficiaries prefer to return to Marawi (68.8%). In terms of preference for local integration, the proportion of those who prefer local integration is a bit higher among MRP beneficiaries (18.5%) than the non-MRP participants (17.8%). A good proportion of the beneficiaries are not yet fully decided at the time of the survey (12.7%).

The team’s findings are consistent with the findings of UNCHR where almost all of the IDPs surveyed (95%) expressed desire to go back to Marawi. The present findings also appear reflective of the findings of Collado where the majority of the participants (70%) indicated their desire to go back to Marawi. The following narratives show prospective considerations for IDPs’ durable solution:

-

“We still have a plan to go back to Marawi because we have a place there. My parents’ house was in my name, and then there was still a place.”

(KII, IDP leader/farmer, Balindong)

-

I think that is one reason [inclusion of HCMs] why some IDPs feel comfortable in the local community and they have an on-going livelihood. But they will eventually return to Marawi because they are from the place.”

(KII, Field Office Manager, Task Force Bangon Marawi)

One of the factors that may have contributed to the response of the IDPs who preferred local integration are the livelihood grants and trainings they have received from MRP. The grants and trainings did not only provide them with economic opportunities while in the local communities but also platforms for interacting and working with other IDPs and HCMs. The following KII responses illustrate the intentionality of MRP in facilitating local integration of IDPs. Moreover, these show the observations of key stakeholders on how the IDPs and HCMs interact with each other:

-

“They [MRP] made sure that the host community and IDPs can work together. IDPs who evacuated here have already settled in our place, and they are already members of the community.”

(KII, MLGU, Bubong)

-

“There are instances in other projects where the sharing of resources to IDPs became an issue. With MRP, the host communities are included. I think that is one reason why some IDPs feel comfortable in the local community and they have an on-going livelihood.”

(KII, Field Office Manager, Task Force Bangon Marawi)

Another factor that influenced the IDPs who preferred local integration as a durable solution are the activities that MRP conducted in reaction to voters’ education and registration. The team finds that MRP has directed substantial efforts in conducting voter’s education and registration activities which resulted in the formalization of IDPs membership to the local communities. For instance, document review data suggest that a number of LGUs have facilitated special voter registration activities that helped formalize the integration of the IDPs in the communities they are residing at present. As part of the results of these activities, 532 youth IDPs and HCMs from the 25 barangays of the towns of Butig, Ditsaan Ramain, Lumbaca Unayan, Lumbatan, Marantao and Poona Bayabao all in Lanao del Sur province participated in the community voter’s education and youth engagement workshops facilitated by the completers of voters’ education training. This resulted to the registration of a total of 242 new voters and transferees.

It is worth noting that the present data on durable solution depict a different picture when compared to the survey conducted by Plan International. Plan’s survey showed that majority of the IDP participants preferred to integrate locally. The changing data on IDPs’ durable solution based on endline survey, MRP durable solution survey, and literature sources suggest that durable solution is still a “fluid” construct among IDPs at the time of the evaluation. Its fluidity is influenced by a host of factors which are beyond the scope MRP.

DISCLAIMER

This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Panagora Group and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or of the United States government.