Findings

CO-CREATION PROCESS

MRP is noted to be the first USAID/Philippines development intervention that underwent a co-creation process. USAID’s principle of co-creation as a design approach is intended to bring people together to collectively produce a mutually valued outcome that involves participatory process assuming some degree of shared power and decision-making. This is affirmed by the following KII narratives:

-

“The co-creation process brought together various stakeholders with multi-disciplinary expertise and experience. Most importantly, ECOWEB and MARADECA who are our implementing partners were part of the process. Their experience in implementing development programs in the area were captured in the process.”

(KII, COP, Plan International)

CO-CREATION PROCESSMRP is noted to be the first USAID/Philippines development intervention that underwent a co-creation process. USAID’s principle of co-creation as a design approach is intended to bring people together to collectively produce a mutually valued outcome that involves participatory process assuming some degree of shared power and decision-making. This is affirmed by the following KII narratives:

The co-creation process served as the foundation in ensuring that the project’s interventions are relevant to the needs of the IDPs and HCMs. The process resulted in the project’s Results Framework (RF) shown in Figure 1. Moreover, interview data indicate that the co-creation process influenced the project design decision of targeting both IDPs and HCMs.

ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT

MRP’s flexibility in programming and packaging of interventions is consistent with USAID’s principle of adaptive management especially that it is operating in an unstable and complex area. Its programming shows that it functions within an “enabling environment that encourages the design of more flexible programs, promotes intentional learning, minimizes obstacles to modifying programs, and creates incentives for learning and adaptive management”. The following KII response highlights MRP’s flexibility and adaptability:

-

“For this particular assistance, adaptive management was very essential. For example, we recognize the color money available. If the money comes from the stream of conflict mitigation, we develop assistance along that stream. It influences target setting. But, year on year it’s demonstrable that the targets are met.”

(KII, MERL Lead, Plan International)

By being flexible in framing and setting targets, MRP was able to reconfigure its interventions to meet the needs of the beneficiaries at given junctures of its implementation. For example, Indicator 10, which was originally framed in the AMELP as the “Number of displaced/HCMs who benefited from social cohesion grants” was expanded in the succeeding years to include additional sub-indicators. By so doing, MRP tapped additional funds from available funding streams from USAID. An example of this is the additional funding for MRP’s COVID Quick Response. This contributed to the continuing accomplishments of the project even at the height of the pandemic. This aspect of the project’s is illustrated by the following KII response:

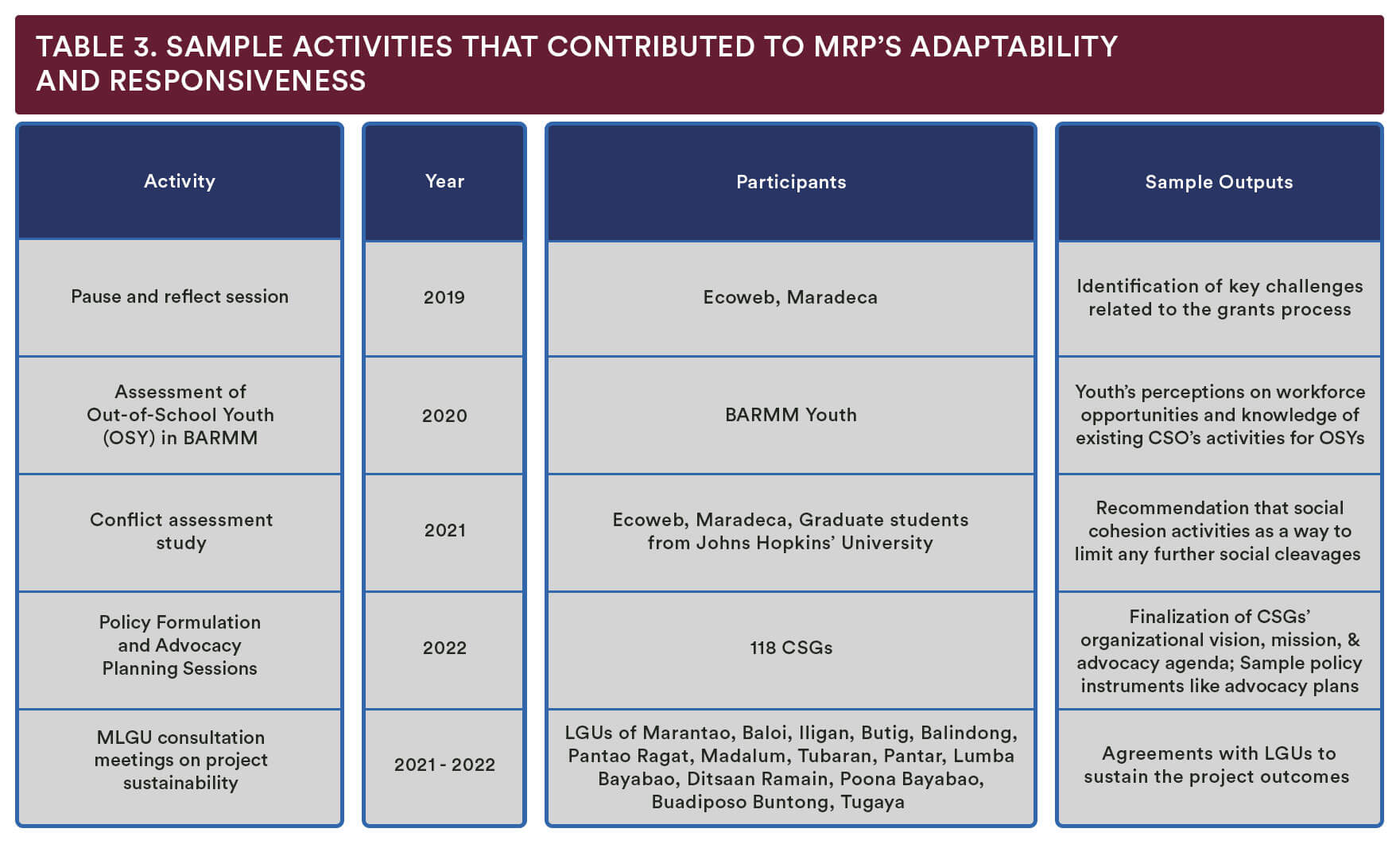

The matrix below shows a sample of activities that MRP conducted to make its programming more adaptive and responsive to needs of the IDPs/HCMs. Refer to Annex 9 for an expanded list.

COLLABORATION WITH LOCAL PARTNERS

MRP was able to adapt the planning and implementation of project interventions over time by regularly engaging local political, traditional and religious leaders. The engagements included resolution of issues that were identified during implementation. The following interview excerpts from MRP stakeholders support this:

-

“What’s good with MRP is that from the start we already talked. In fact, during the early stages, they always give me updates. Until now, we consider Plan International as a significant partner especially on business and livelihood.”

(KII, Field Office Manager, Task Force Bangon Marawi)

-

“MRP has helped a lot in providing programs for the IDPs and HCMs. They did a great job in addressing the needs of the beneficiaries. They worked with us closely in the implementation of the programs.”

(KII Buadiposo Buntong, LGU MPDC)

MRP is unique in its interventions as it provided non-cash assistance to the project beneficiaries. KII data suggest that one of the inputs that contributed to this emanated from a prominent government leader who was consulted at the outset. The evaluation team deems that the foregoing findings helped address the baseline recommendation, which encouraged MRP to engage the LGUs during the pre-entry stage of social cohesion activities to strengthen the relationships among IDPs, HCMs, and barangays. Box 1 contains the story shared by a municipal administrator how MRP harnessed its relationship with their LGU.

Box 1. Harnessing LGU partnership for relevance, effectiveness and sustainability

The Municipality of Bubong, Lanao del Sur is a second class municipality with a population of 26,514. At the height of the Marawi Siege, Nabillah R.H. Abdulhakim, served as the Municipal Administrator and worked closely with MRP’s implementing partner, Maradeca, which has been a partner of the local government in peace and development efforts for many years.

She recognized as important MRP’s approach in targeting both the IDPs and HCMs. Likewise, she lauded how MRP went down to the communities and asked people about their priority needs. “MRP asked people about their needs. The women expressed they needed support for dressmaking to earn income. During the graduation ceremony, I saw the products of women beneficiaries. The women worked hard and committed to supporting their families.”

She strongly believes in the importance of sustaining the gains of MRP by strengthening the CSGs and increasing their participation and voice in LGU processes. “We are helping the youth and women federations in their accreditation in the municipality. They already have by-laws and policies which are the requirements for accreditation. They can become members of our local special bodies. The women can be registered as cooperative and the youth can be accredited by National Youth Commission. This is important for their representation.”

BENEFICIARY STORY OF RELEVANCE

MRP beneficiaries shared stories about how the interventions they have received from MRP ameliorated their situation and helped meet their needs especially during the height of the pandemic. The following KII excerpts portray this:

-

“For me, the grant that MRP provided to us was appropriate because it also suited our ability as women. In particular, the sewing machine that they gave us helped women in our area to earn income.”

(KII, IDP Leader, Ditsaan Ramain)

-

“The in-kind grant from MRP was really a big help to my pharmacy business. It was also timely for the sanitary needs of my customers during the time of the COVID-19.”

(KII, BRG Grantee, Marawi City)

MRP has implemented mechanisms to address social inclusion issues. One of the key mechanisms that MRP employed to address barriers and opportunities to women’s participation in economic and social cohesion activities was the establishment of gender-specific CSGs. Around 278 all-women CSGs have been established. These CSGs played significant roles in community conversations, prioritization workshops, participatory conflict assessments, and TNAs, which informed the design and implementation of MRP activities.

Another mechanism was the development of community champions from the youth, women, and religious leaders. The efforts of the community-based champions helped shape the decision-making and programming of the target barangays in addressing child protection and GBV issues. In total, MRP trained 82 CSG champions who also organized GBV community roll-out sessions reaching 879 CSG members.

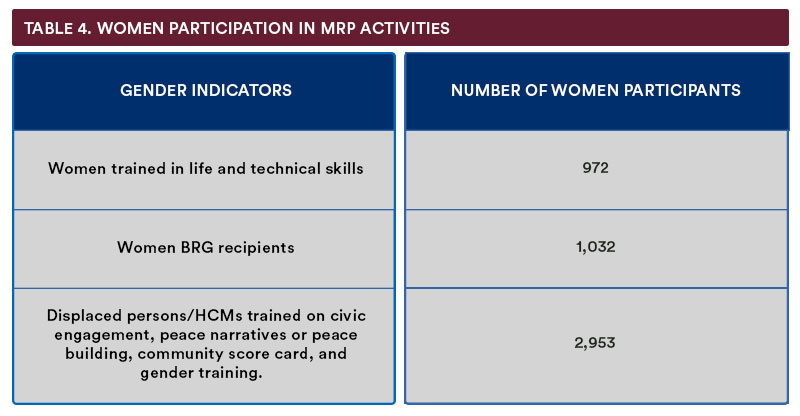

Furthermore, document review data suggest that 51% of beneficiaries in Year 3 are women. Currently, 43% of the CSGs are all-women, while 59% are led by women. These show that women have been taking the lead in most of MRP’s major activities. While participation in activities does not immediately translate to women empowerment, their involvement forms part of the essential initial steps in the process of confidence-building. The table below shows the project’s performance in terms of gender-related accomplishments for Year 3.

It is worth noting that the conditions within which women struggle still persist despite good participation numbers among MRP women. Document review data indicate that women are still confronted with the double burden of working to earn a living and at the same time performing domestic work. It has been noted that gender-based violence (GBV) still exists. Moreover, project reports indicated that the prevailing culture of silence and pressure for women to go along and accept amicable settlements pose challenges to the gender equality champions that MRP developed. However, MRP’s continued implementation of GBV-related interventions during the pandemic addressed the noted rise of gender-based violence during this period. This rise has been highlighted by the UN Women organization (2021) as shown in the organization’s explanation below:

-

“Gender-based violence, already a global crisis before the pandemic, has intensified since the outbreak of COVID-19. Lockdowns and other mobility restrictions have left many women trapped with their abusers, isolated from social contact and support networks. Increased economic precarity has further limited many women’s ability to leave abusive situations.”

The following narratives lend support to the efforts placed by MRP on addressing the needs of the women including those that are related to GBV:

-

“MRP asked people about their needs. The women expressed they needed support for dressmaking to earn income. During the graduation ceremony, I saw the products of women beneficiaries. The women worked hard and committed to support their families.”

(KII, MLGU, Bubong)

The story of an all-women CSG member in Box 2 shows how the grant they received from MRP empowered them to meet the economic needs of their families.

BOX 2. FROM STRUGGLE TO EMPOWERMENT: STORY OF WOMEN’S RESILIENCE

Rainidah S. Macadato evacuated in 2017 to nearby Bagoinged Ditsaan Ramain, Lanao del Sur to flee from the bitter clashes in Barangay Marinaut West, Marawi City. She remembered it was extremely difficult at first. They lived in the gym with other displaced families they hardly knew. Buy they needed to find ways to survive and relied on the help of the government and other groups.

In September 2019, Rainidah joined the all-women community solidarity group, Newtonians Women’s Dressmaking that the local implementing partner, Maradeca, organized in their barangay. She attended many organizational meetings in preparation for the community micro-grant. She was designated as CSG Treasurer. In December 2020, they were happy to receive their livelihood support from MRP which included 33 sewing machines and fabric. “For me, the grant that MRP provided to us was appropriate because it also suited our ability as women. In particular, the sewing machine that they gave us helped women in our area to earn income.”

“The hijab we made from the fabric earned us Php19,950.00. So far, our profit has reached Php40,000.00. All members received their share. We are now on our fifth cycle.” While Rainidah and other members of the women’s CSG have been thankful to MRP, they also recognize the importance of setting up policies to ensure the sustainability of their operations.

“We develop policies on how to manage our investment and income. We set some rules on the percentage sharing of income between those who are involved and the rest of the CSG members. 20% of the income will go back to our capital investment, and 10% is also shared with all members even if they are not working on the sewing machines. This way they continue to participate in our CSG. We believe we need to do this to sustain what we received from MRP. Through this, we hope to increase our operations.”

The team finds that the composition of the Community Solidarity Group (CSG) is pivotal in addressing the needs of the IDPs and HCMs. The CSG is the primary mechanism through which the MRP identifies and solicits grant proposals. The role of the members in identifying and prioritizing community needs, suggesting opportunities for collaborating to address these needs, and for identifying potential community tensions is essential.

The MRP team together with the local consortium partners (LCPs) identified key activities required from pre-community entry to grant proposal submission. The participatory processes that the LCPs facilitated served as opportunities to strengthen the relationships of CSG members. As such, the CSGs are helping build social cohesion and a sense of common understanding among members. From September 2018 to March 2022, MRP organized 665 CSGs. Of the total, 552 are intact while 113 are dissolved. Refer to Annex 10 for the community engagement and grant application cycle.

The evaluation team identified models of successful and sustainable CSGs as follows:

- Active CSGs that have received grants and have successfully implemented their projects;

- Active CSGs that have received grants even if they were not successful in implementing their projects;

- Active CSGs that are yet to receive their grants but remain hopeful to eventually receive them; and

- Active CSGs even with disapproved grants and with no chance to receive them.

The factors contributing to these models include established community leadership, existing social relationships, level of group maturity, socially cohesive local environments, and inherent and acquired skills in managing their projects. Conversely, the examples of unsuccessful CSGs include the following:

- Dissolved CSGs even after receiving grants and successfully implementing projects, which happened mostly in urban areas;

- Dissolved and frustrated CSGs that have not received any grant; and

- Dissolved CSGs not able to successfully implement projects due to various factors including lack of management skills.

Document review data show the following as reasons behind the CSG’s dissolution: Presence of Rido (feud between families/clans) or conflict in the area; CSG members/leaders lost interest and expressed to discontinue their participation; CSG declared themselves as dissolved after dividing grants equally, and no longer meet as a group; CSG members returned to Marawi and/or transferred to other places due to livelihood/work reasons; or No one from the CSG can be contacted/traced.

The narratives below highlight the value of the CSGs based on the perspective of the selected stakeholders:

-

“I like MRP’s approach of CSG organizing. They included both IDPs and the members of the host communities. I believe that such organization is appropriate for socio-economic intervention.”

(KII, Asst. Regional Director, DTI, Lanao del Norte)

MRP’s development interventions complemented the functions of Task Force Bangon Marawi (TFBM). The project’s interventions are particularly relevant to TFBM’s role in providing an environment conducive to the revival of business and livelihood activities as stated in Administrative Order No.3 s.2017. MRP has been pivotal in fostering economic recovery by taking an active role as a member of TFBM’s Subcommittee on Business and Livelihood.

Moreover, MRP contributed to the formulation and implementation of the TFBM’s Sustainability Plan for Scaling Up Business and Livelihood of Marawi IDPs. The plan serves as platform to scale up the interventions relating to business and livelihood and ensure their sustainability. The following KII narratives from provide insights how MRP complemented government programs:

-

“The first convergence of DTI with MRP, as the undertaking was economic, particularly on the area of legitimization of the business – registration, business name, input/lectures from DTI onwards to securing business permits.”

(KII, Asst. Regional Director, DTI, Lanao del Norte)

-

“I always say to the people that infrastructure assistance from the government will end. You [IDPs and HCMs] are provided with livelihood assistance so you will not depend on government support. It fits the context because the Maranaos are business oriented.”

(KII, Field Office Manager, Task Force Bangon Marawi)

Moreover, MRP’s business and livelihood grants, which benefitted a number of cooperatives in Lanao del Sur and Norte with IDP and HCM members are in harmony with the government’s project dubbed as “Marawi Rehabilitation through Cooperativism Project.” The Cooperative Development Authority (CDA) under the aegis of TFBM implemented the project in 2018. The team finds that MRP contributed to the goal of this project of reactivating the cooperatives in Marawi City to provide business and livelihood opportunities to the residents.

On a different vein, MRP assisted various LGUs in addressing COVID-19 through its COVID Quick Response initiative at the onset of the pandemic. It provided COVID-19 essentials (e.g., PPE, masks, thermal scanners, and disinfectants), conducted information, education and communication activities, capacity building and technical training (e.g. treatment facility management, and specimen collection and handling). This is corroborated by the KII narrative shown below:

-

“From the start of the pandemic, MRP actively coordinated with the Inter Agency Task Forces (IATF) of the different LGUs. Specific attention was accorded to participation in the Lanao del Sur (LDS) IATF as it covered the majority of MRP project areas. MRP was invited and participated in a number of the LDS IATF meetings.”

(KII, COP Plan International; AR 2020, p.32)

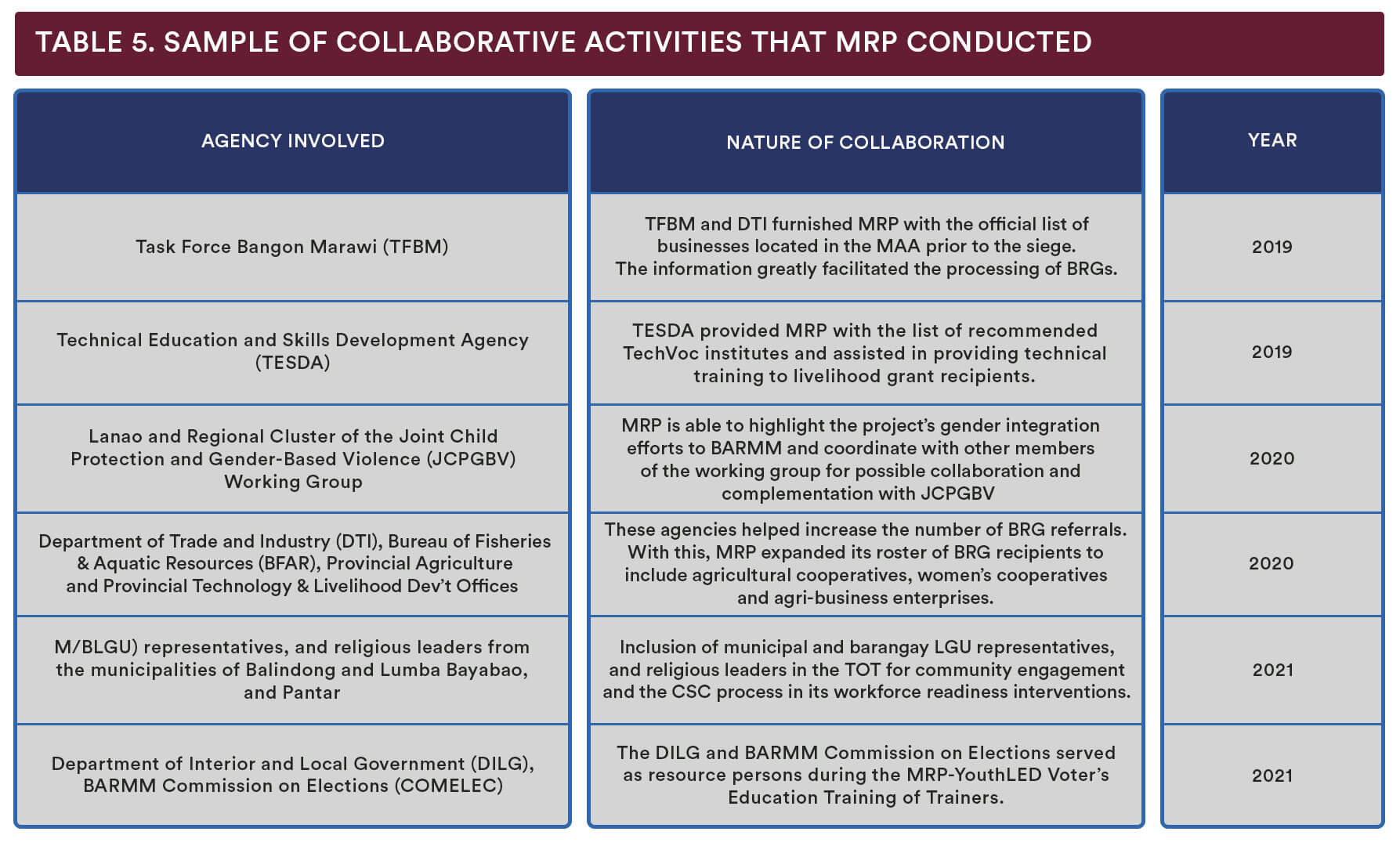

Table 5 shows a sample of the collaborative activities between government agencies and MRP. Annex 11 presents an expanded list.

USAID’s 2013-2018 Country Development Cooperation Strategy (CDCS)

- Development Objective 1: Broad-Based and Inclusive Growth Accelerated and Sustained

- Development Objective 2: Peace and Stability in Conflict-Affected Areas in Mindanao Improved

- Development Objective 3: Environment Resilience Improved

MRP is relevant to USAID’s 2013-2018 (extended through 2019) Country Development Cooperation Strategy (CDCS). In particular, it is relevant to the objective of improving peace and stability in conflict-affected areas, particularly in Mindanao (Development Objective 2). In terms of the specific objectives set to meet this broader goal within the context of the Marawi siege, MRP helped in addressing the objectives of transitioning IDPs to social and economic stability (Objective 2) and establishing the conditions for local governments and communities in and around Marawi to address their long-term rehabilitation needs (Objective 3).

USAID’s 2019-2024 Country Development Cooperation Strategy (CDCS)

- Development Objective 1: Democratic Governance Strengthened

- Development Objective 2: Inclusive, Market-Driven Growth Expanded

- Development Objective 3: Environmental and Community Resilience Enhanced

The positive changes in the social cohesion indicators (i.e. polarization and public participation) as shown in the endline survey results contribute to the achievement of the objective of strengthening democratic governance (Development Objective 1) in the 2019-2024 CDCS. In particular, the team finds that MRP’s development interventions are relevant to the realization of building more responsive local governance (IR 1.4) considering that “USAID anticipates that during this CDCS, civil society will become more engaged, better networked, and more inclusive as they connect across regions and sectors”. The noted positive changes in social cohesion provide support to the enhancement of environmental and community resilience (Development Objective 3) particularly in increasing social connectedness (IR 3.3.2).

These findings support USAID’s belief and approach that “Increasing social connectedness and social cohesion is one of a set of responses to strengthen community resilience. USAID will work through civil society to build formal and informal networks that include populations vulnerable to such threats and tie together areas affected by shocks and disasters, including violence and conflict.”

The economic outcomes of the project are essential to the expansion of inclusive, market-driven growth (Development Objective 2) particularly in improving private enterprise development (IR 2.4.1). The team also finds that MRP’s approach of tapping cooperatives in its business and livelihood grants is consistent with USAID’s perspective which suggests that: “Cooperatives play a critical role in addressing livelihood challenges, especially in rural areas, and benefit host communities through various social initiatives. A huge potential exists for small and medium-sized enterprises as development partners.”

DISCLAIMER

This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Panagora Group and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or of the United States government.