Findings

Sustainability refers to the ability of a local system to produce desired outcomes over time. Discrete projects contribute to sustainability when they strengthen the system’s ability to produce valued results and its ability to be both resilient and adaptive in the face of changing circumstances. MRP’s sustainability strategy followed USAID’s Local Systems Framework that facilitated collaborative engagements among project beneficiaries, various local government units, government agencies, civil society organizations (CSOs), and the private sector. The framework defines how collaborative delivery of program assistance though local systems can increase the sustainability of development benefits. MRP operationalized this model in a number of ways, which included:

- Forging partnerships between and among the relevant project stakeholders that strengthened their buy-in to the project;

- Establishing sustainability policies and strategies that supported grantees in ways that qualifies them for future government support and links them to markets;

- Building, empowering and formalizing community solidarity groups as a mechanism for them to continue to serve their members after the conclusion of MRP; and

- Promoting socially inclusive processes in the implementation of its development interventions which included both IDPs and HCMs.

These strategies are discussed in further detail in the section that follows.

MRP forged partnerships and synergies between and among the relevant project stakeholders. MRP’s engagement with various strategic actors in the implementation of its development interventions even during the early stages of the project is crucial in sustaining its outcomes. This strengthened stakeholders’ buy-in to the project.

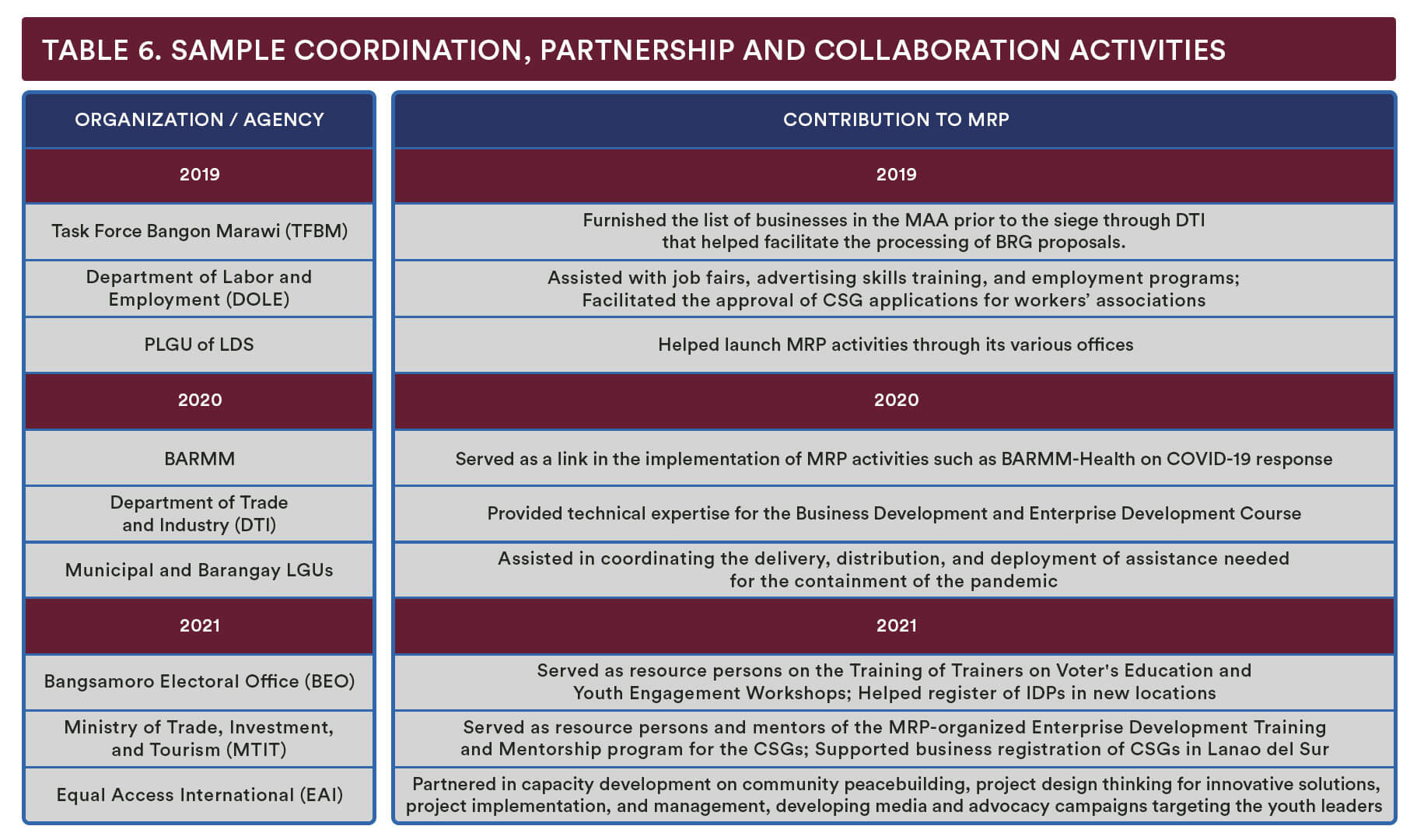

Table 6 contains a sample of the coordination, partnership, and collaboration activities that MRP forged with various stakeholders. Refer to Annex 13 for an expanded list.

The close engagement and buy-in from stakeholders are noted to be essential factors for the sustainability of the outcomes of the project. These factors facilitated alignment of priorities, strategies, and resource sharing. The following narratives illustrate how MRP has established synergy with other strategic actors in the rehabilitation of Maraw

-

“TFBM and MRP have collaborated in facilitating activities. An example is the series of trade fairs. In these fairs, we really select the beneficiaries so that they will have the opportunity to sell their products. We also have the business forum, Lanao del Sur Business Forum. This is for providing the beneficiaries link to the market. We have a series of activities to help those who received assistance. We are collaborating to expand the market, possibly outside Marawi.”

(KII, Field Office Manager, Task Force Bangon Marawi)

-

“For the BRG distribution of in-kind inventories, DTI complemented by training the individual entrepreneurs along the areas of business and financial management, marketing – pricing, costing.”

(KII, Asst. Regional Director, DTI, Lanao del Norte)

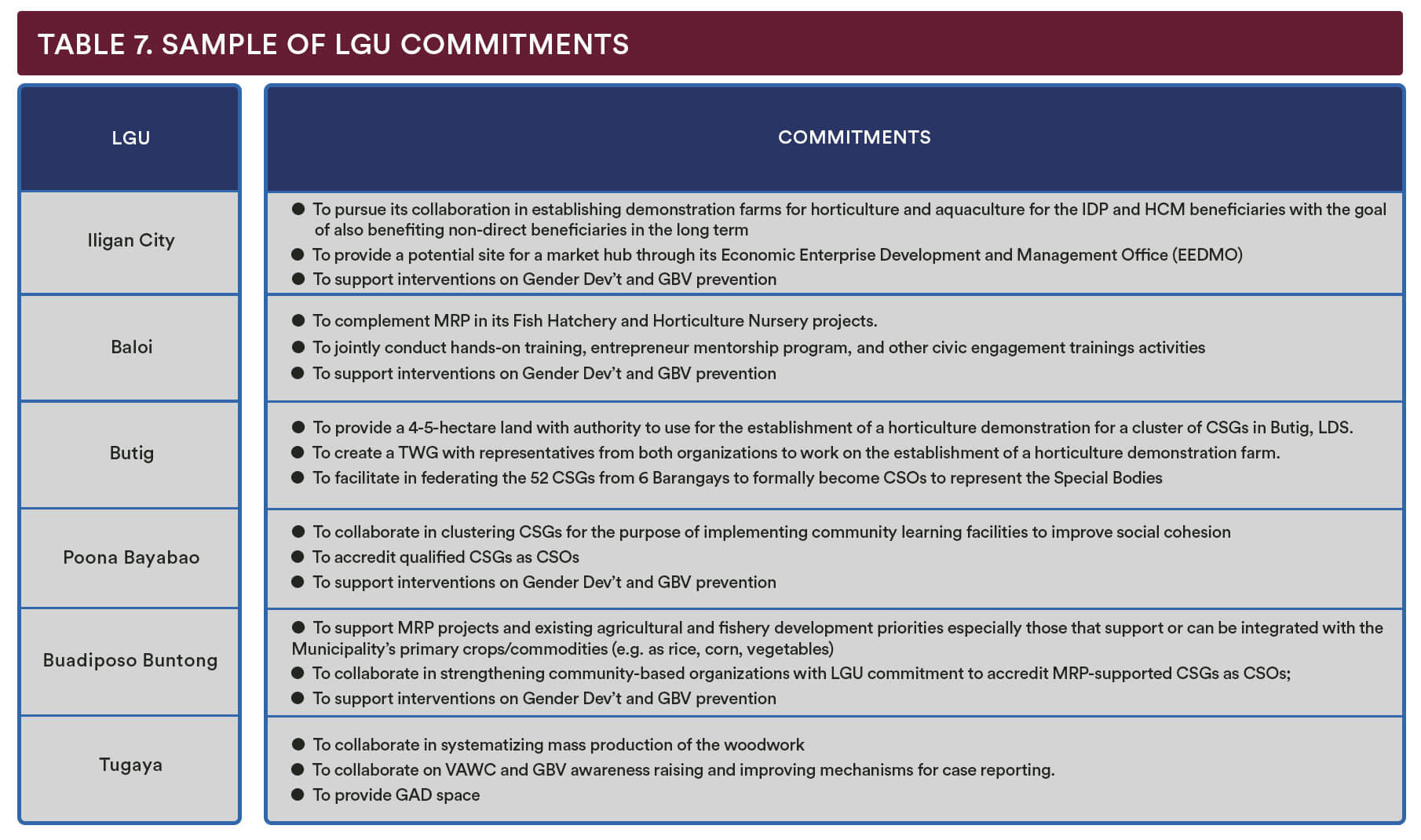

Moreover, the team finds that MRP’s intentionality in engaging with LGUs resulted to sustainability commitments. The LGUs have expressed support and commitment to help sustain the gains of the project in their respective areas. Table 6 outlines a sample of the sustainability commitments that MRP has generated from various LGUs. Annex 14 shows an expanded list.

GRANT-RELATED POLICIES (E.G., BUSINESS REGISTRATION, SUSTAINABILITY PLAN, TRAINING)

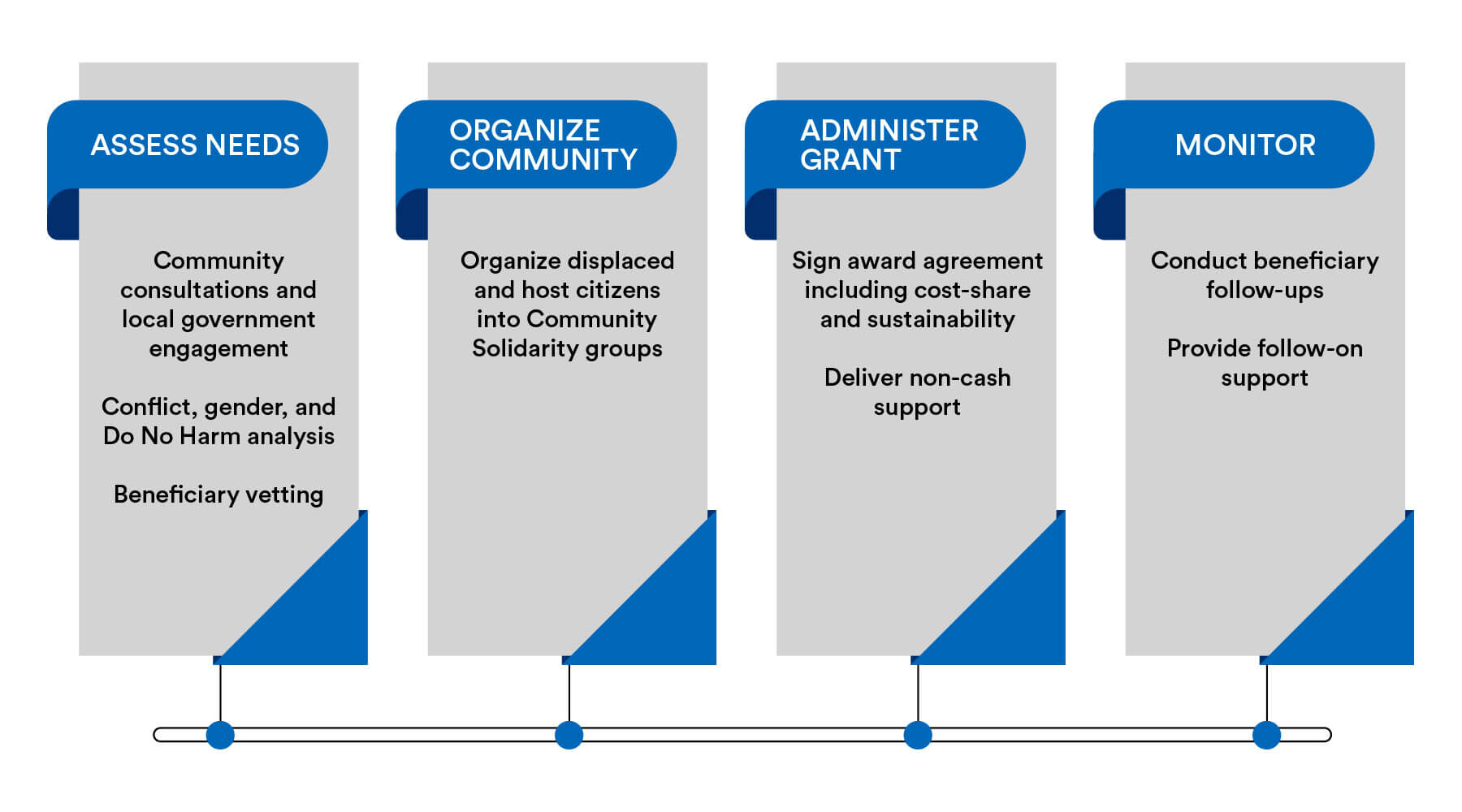

MRP has established internal mechanisms that are essential in promoting the sustainability of project gains. In particular, it has stipulated that sustainability principles be incorporated into the administration of grants in ways that increase the likelihood of the program’s benefits being sustained beyond the life of the project. MRP’s Grants Manual illustrates the processes and procedures from the preparation of concept notes and grant proposals to endorsement and approval of grant proposals and kick-off with the beneficiaries. The process is illustrated in the figure below:

Part of the grant administration (3rd phase) is for prospective grantees of business recovery grants (BRG) and community micro grants (CMGs) to have their business/livelihood to be duly registered with the government. The team finds that this policy is essential for sustainability since it qualifies the beneficiaries to avail of possible government support when MRP ends. Moreover, part of the grant administration which is essential for sustainability is the need for grantees to sign a sustainability agreement, part of which is the sustainability plan that they need to develop.

The implementing partners, MARADECA and ECOWEB, made necessary follow-ups relating to continuity and sustainability, as well as, business improvement training and organizational capacity-building. Monitoring is done through FLUXX. As of March 2022, there are 394 BRGs, and 368 CMGs. Almost all BRGs are still existing and are recovering. Many CMGs are likewise progressing and incumbent on the existence (intact) and non-existence (dissolved) of the CSGs organized.

VALUE CHAIN APPROACH (VCA)

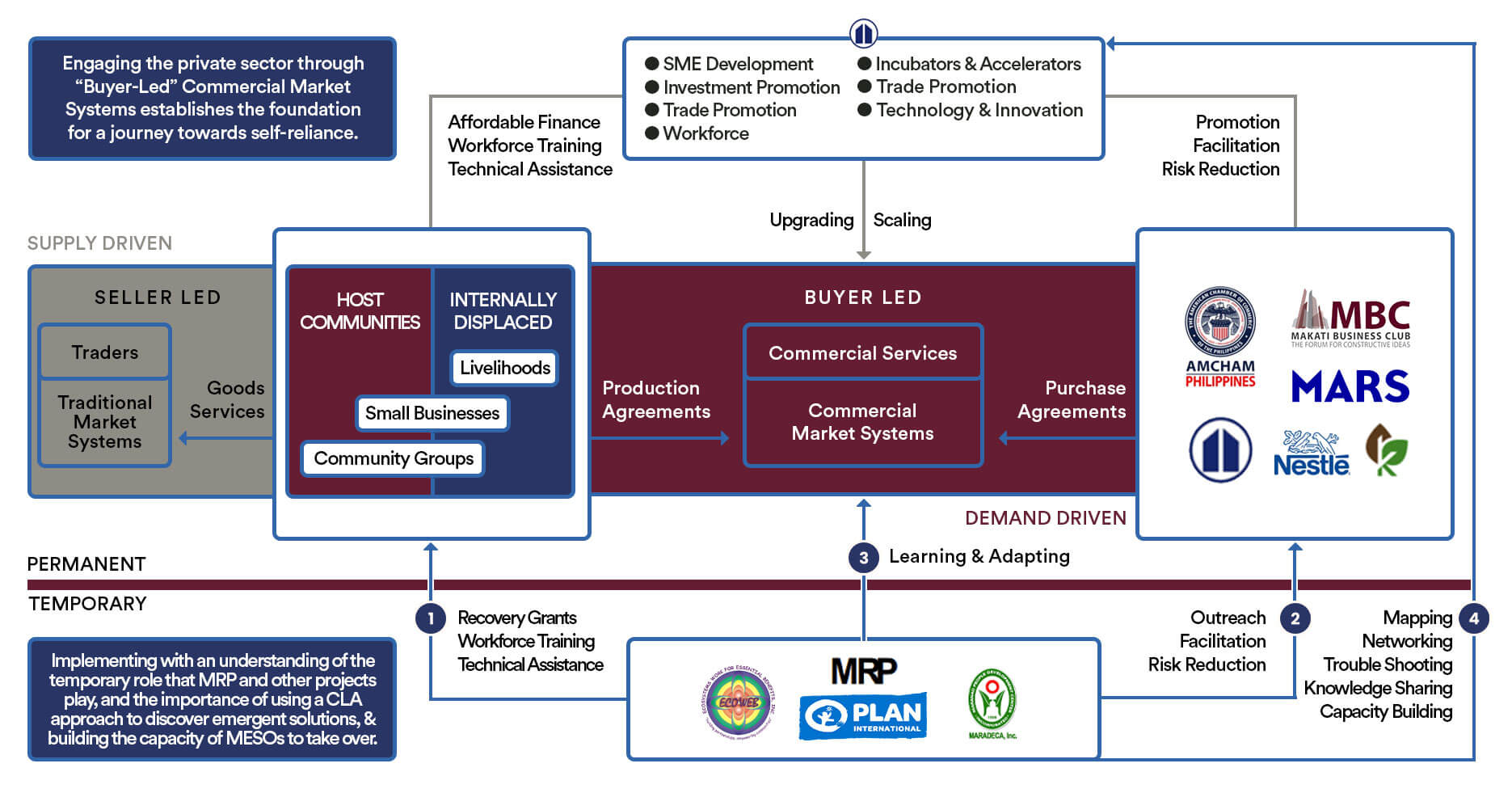

MRP’s value chain prioritization is a potential sustainability mechanism since it mainstreams promising (nascent) products in view of a demand-driven market. Among MRP’s value chain priorities are aquaculture, horticulture, and weaving products. Figure 17 illustrates the framework of MRP’s overall VCA approach. The framework depicts four work streams of MRP intervention and activity, which are indicated in blue circles. MRP has implemented activities that are relevant to the four streams identified in the framework. Moreover, LGUs have expressed support to the VC priorities such by establishing demonstration farms, providing market hubs, integrating farmers’ produce to municipalities’ primary crop commodities, and providing technical expertise.

However, unless a real commitment from the buyers at the national and international market is reached, the trade expos that were conducted may not be enough to scale-up the ventures of the grantees. This correlates to some of the key challenges already identified in the MRP VCA concept notes namely, scaling production and delivery, bringing commercial partners into the system, and unleashing of the meso-space (Schneider, 2020).

Since the value chain was introduced only in the 2nd year and selected CSGs were identified and given value chain grant support only in the 3rd year, the measurement of success cannot be ascertained at the time of evaluation. Value chain development and promotion take time. As MRP exits and as the CSGs are evolving into a more functional and purposive business organizations, further interventions from government and non-government further are necessary for the CSGs to be competitive in a market-driven economy.

While the team supports the notion that VC priorities are well-thought market-driven interventions, beneficiary ownership is noted to be low as the CGG clusters are still learning the technology (e.g. with aquaculture particularly freshwater fish tilapia) while simultaneously undergoing organizational transformation (e.g. being a cooperative). Thus, measuring VC progress and success goes beyond the project life of MRP.

DEVELOPMENT AND TAPPING OF ASSOCIATIONS AND COOPERATIVES

Cooperative as a business organization is another sustainability direction that the MRP’s CSGs are trying to develop. A number of CSGs are now registered as associations with DOLE, a stepping stone towards formal business engagement, with their development and promising produce in aquaculture and horticulture, CSGs are now talking about forming cooperatives, a scaling-up towards a real enterprise development and market mainstreaming.

Of the 28 CSGs from eight municipalities engaged in horticulture, food retail and weaving, more than half of them have registered or in the process of registering are associations with DOLE. This will also be true with the recently organized clusters of associations (registered or in the process) for aquaculture in the municipality of Balindong that is in the process of registering into a cooperative. With MRP’s exit, concerned LGUs through its Committee on Enterprise Development (or similar body) together with government line agencies could help these CSGs towards a formally organized associations or cooperatives. The DOLE could assist the associations and the CDA could help the cooperatives.

Box 6 illustrates how a group of women decided to transform their CSG into a cooperative. As a result, their CSG is thriving and is helping its members meet the needs of their families.

BOX 6. ECONOMIC SUPPORT THROUGH COMMUNITY COOPERATIVE

Mocrinah A. Mohammad, Chairperson of Dayanan Handicraft Coop based in Marawi, could only remember in pain the devastation of the Marawi siege. She remembered the economic impact on her family and neighbors due to the loss of livelihoods and the stoppage of formal and informal businesses.

In January 2019, Mocrinah decided to set up the cooperative with 25 other women and youth weavers from her community. They submitted a business recovery grant proposal to MRP and in 2021, they received two sewing machines, threads, and cloth. Using their home as an office and production base, they produced various handicrafts such as bags, face masks, and other customized products. The coop members received income based on their production volume. Mocrinah tapped also into her social networks and friends to generate additional support and for marketing.

She has these great words to say: “If we compare our situation before and now, now is better. For example, the two sons of our coop members who stopped school for two years are now back to school because of the income we have from the handicrafts that we make.”

Mocrinah understands the challenges in sustaining the operations of the cooperative, especially in product marketing. She looks forward to training more young members so that they can manage and sustain the operations of the cooperative.

MRP has devoted substantial institutional capacity development efforts to empower the Community Solidarity Groups. These efforts included organizing them as recognized community associations, training them on civic engagement for effective public representation, as well as on community scorecard to identify their priority needs and plan and implement projects to address their needs. MRP also consolidated CSGs to become federations and become CSOs, and supported them to become social enterprises.

CSG CAPACITY BUILDING

MRP has devoted substantial efforts to building the capacities of the CSGs. The effect of these efforts can be seen in the following manifestations:

- Majority of the CSGs (83%) are active (552 of 665 CSGs) based MRP CSG database;

- Majority of CSGs (71% or 139 of the 193 CSGs assessed) have organizational capacities that are considered functional to effective based on the Rapid Organizational Capacity Assessment that MRP conducted. These CSGs have the ability to manage their current grants; and

- Financial capacities of CSGs and its members involved with livelihood projects have been improved.

TOWARDS BECOMING CSOS

The transformation of the CSGs to formal organizations (e.g. CSOs) is vital in sustaining the outcomes of the project. To this effect, the following findings are noteworthy:

- MRP provided technical guidance and capacity-building support through the local implementing partners and external consultants in forming the CSGs into sectoral advocacy groups and providing them with learning sessions on policy formulation and advocacy planning. These efforts resulted in 118 CSGs composed of 2,720 members federating themselves to form 17 CSG sectoral CSGs (women, youth, and workers / farmers). These CSGs have evolved from being purely a mechanism for the delivery of community economic and social cohesion micro-grants to becoming sectoral advocacy groups.

- The CSG federations developed their organizational vision and mission as grassroots-based organizations, and their organizational values as social movements of women, youth, farmers, or workers in their respective localities. MRP also supported them in securing their accreditation and recognition by the LGU and national agencies such as the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE).

- The CSG sectoral federations identified and prioritized their advocacy agendas to advance priority issues of their respective communities, which focus on GBV prevention and women’s empowerment, youth education and employment, farmer’s access to capital and market, conflict transformation, and workers’ rights. Finally, MRP provided them with technical guidance in drafting policy instruments, such as resolutions and policy advocacy plans. They will use these advocacy plans to engage relevant government bodies for example the Local Youth Development Council, the Local Committee on Anti-Trafficking (LCAT) and Prevention/Response to VAWC, Local Council for the Protection of Children, and the Local Development Council.

TOWARDS BECOMING SOCIAL ENTERPRISE

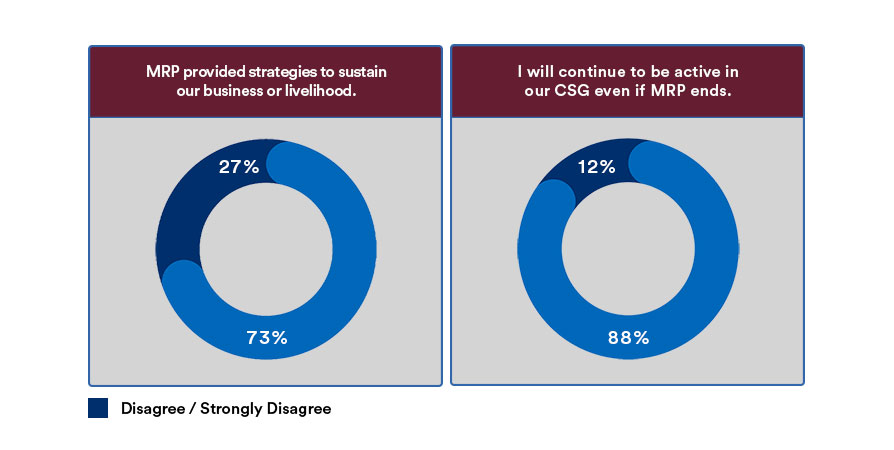

Endline survey data shown in Figure 18 indicate that majority (73%) of the beneficiaries agreed/strongly agreed that MRP provided strategies to sustain their business/livelihood. Moreover, a significant number of them (88%) expressed that they will continue to be active in their CGS even if MRP ends. This is essential not only in achieving financial gains for their businesses but in maximizing their social impact through the realization of their organizational aspirations.

The following narratives illustrate the commitments of the beneficiaries to continue and sustain the gains they have achieved through the development interventions of MRP:

-

“Up to the present, our members continued to earn profits and increased the inventories and sales of our individual sari-sari stores. Our CSG still exists and we continue to meet.”

(FGD, Women CSG Members, Butig)

-

“As a women’s community solidarity group, we committed at the start to sustain what MRP gave to us. We knew that what they gave would really help us.”

(KII, IDP Leader, Ditsaan Ramain)

MRP endeavored to be socially inclusive in implementing its development interventions. MRP’s project activities provided opportunities and spaces for greater engagement and collaboration between and among IDPs and HCMs. In particular, the requirement for IDPs and HCMs to do joint analysis and planning sessions in order to access community grants and collectively benefit from them helped address tensions over limited resources and reinforced their social cohesion.

This core strategy is key in sustaining the gains of MRP and in scaling up project outcomes. This strategy has started to gain traction among development agencies and “the results have been positive and widespread, appreciated by communities that would otherwise have suffered greater deprivation and stress. Not only do such programs promote greater community harmony and lessen the risk of conflict over resources, but they can also be cost-effective life-saving mechanisms to vulnerable individuals.” While this strategy has leveraged positively the collaboration of IDPs and HCMs to work together in addressing their collectively identified priority issues, it remains important to ensure that the needs and interests of IDPs, given their higher vulnerability, have to be prioritized. The needs of IDPs and HCMs are far wide and complex. In most cases, MRP’s interventions addressed their shared needs through community grants and other relevant project processes. Addressing the distinct needs of beneficiaries remains complex and requires more resources and time.

The value of IDP-HCM targeting as project beneficiaries can be gleaned from the following narratives generated from the interviews:

-

“The beauty of MRP is that not only the IDPs from Marawi were targeted, but also the host communities. They made sure that the host community and IDPs can work together. I think this approach is important – that they both benefit from the projects.”

(KII, Municipal Administrator, Bubong)

-

There are instances where the sharing of resources to IDPs became an issue. With MRP, the host communities are included. I think that is one reason why some IDPs feel comfortable in the local community because they have already assimilated there and they have an ongoing livelihood.”

(KII, Field Office Manager, Task Force Bangon Marawi)

The evaluation team shares the following reflections and lessons learned in the conduct of this evaluation:

- Intentionally targeting idps and hcms provided the project beneficiaries with myriad opportunities to work together, harness relationships, and address common issues. Moreover, the participatory processes carried out by MRP forged effective engagement of both lgus and csgs. On one hand, these mechanisms increased idps and hcms’ sense of ownership and commitment to engage in project activities. On the other hand, the lgus have become more open in allowing spaces for greater civic engagement of idps and hcms in the barangay and municipal governance structures.

- Mutually reinforcing economic development and social cohesion outcomes are integral to addressing the needs of idps and hcms in highly complex environments. Mrp’s experience showed the importance of intentionally incorporating these two outcomes to address economic development gaps and socio-cultural and political dynamics.

- Efficiency in the delivery of assistance for emergency situations should inform the development of project protocols and requirements. In line with the principles of adaptive management, there needs to be a balance between accountability and timely delivery of appropriate response to project beneficiaries. In highly complex situations, the being efficient in delivering project interventions to vulnerable and often-frustrated beneficiaries could lead them to actively engage in project processes and increase their sense of hope for durable solutions.

DISCLAIMER

This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Panagora Group and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or of the United States government.